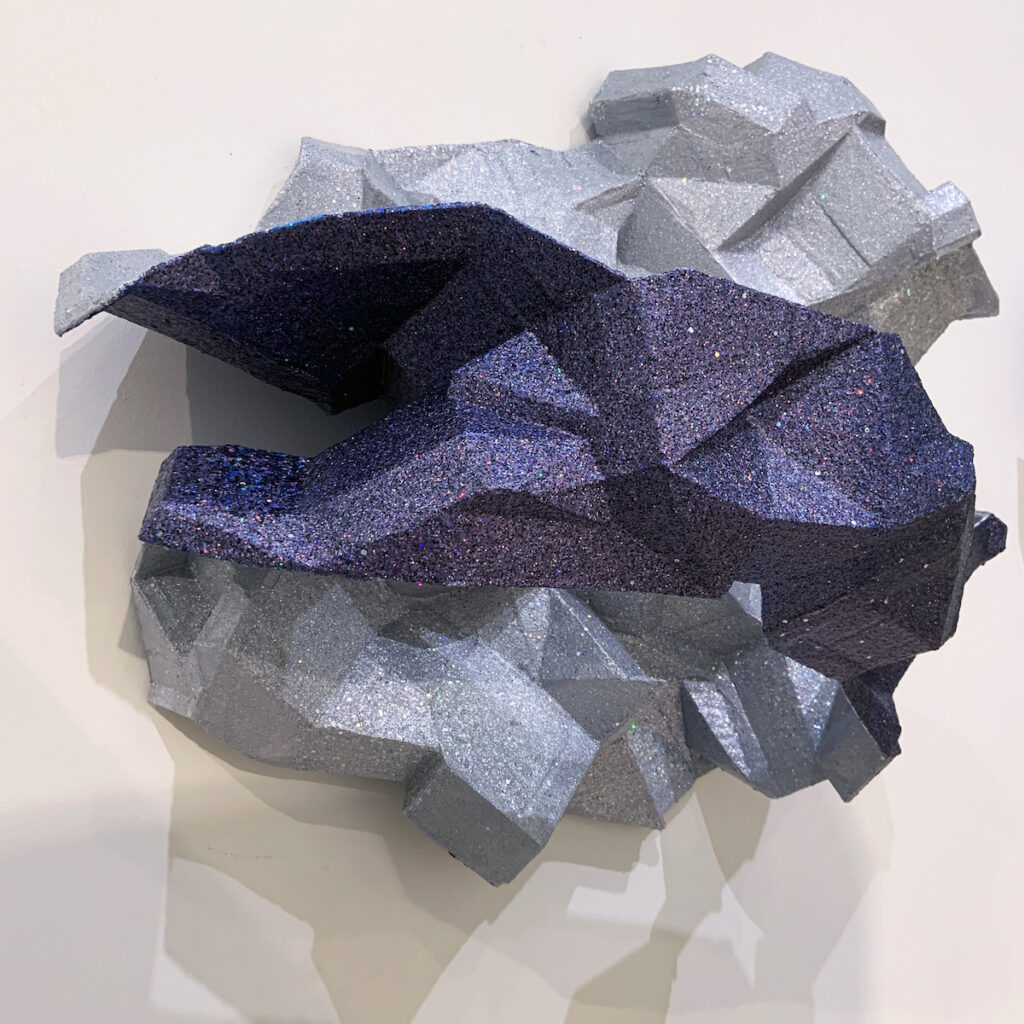

2021. Cardboard, glitter, glue.

Penny Stocks is constructed from the materials I had around me: Amazon boxes, spackle, paint, and holographic glitter from previous projects. Each form is the result of reactions rather than a predetermined goal. The purpose of skinning the forms with glitter is to complicate the objects’ association with high and low craft.

I often think of the giant craft fairs at my elementary school in Kentucky, loud rooms lined with women makers participating in a material exchange free from markets and craft hierarchies. With the emphasis on trade and celebration of whatever items lined those tables, these events were magical in their own autonomous acts of demarcating and communicating worth. Temporary closed-circuit economic exchanges were accessible by any maker who could borrow a table. They were the trading floors of penny stock appropriations.

The term “penny stocks” comes from the saying trading pennies on the dollar used to describe the Security Exchange Act designation of stocks purchased for less than $5 dollars. These prices create accessible entry points for individuals with less capital and because of this, penny stocks are seen as denigrators in the market. The consequence of this low-class association and mass accessibility is a market that is under-regulated and ripe for fraud.

The most common fraud practice with these stocks is called pump-and-dump. Pump-and-dump is where large quantities of stocks are purchased at very low prices and their value is raised in the eyes of the market through “misleading positive statements and artificial inflation” (Wikipedia) only to be sold en mass once the value of the stocks is higher than the purchase price.

Side-stepping the conversation on how the secondary art market is profoundly committed to ideas underlining pump-and-dump, what draws me to these stocks as an intellectual exercise is the concept of the pump. Pump-and-dump is considered deceitful, fraudulent, and inevitable. But when taken out of the context of the market and placed on top of human relational systems, the action of pumping could be tied to the actions demanded in the common expression of ‘leaving a place better than you found it’.

‘Leaving a place better than you found it’ and ‘a job worth doing is a job worth doing well’ were two of my Kentucky grandmother’s favorite life sayings. Where the last one is a lesson in the dignity of labor and craft, Leave a place better than you found it is an action of investment and wealth creation, wealth that defines the limitations of market values.

The connection between pumping and my work is found in the repetition of labor I rely on to make the work. The labor is an investment, it is an act of raising the value of the materials I work with. A value not measured in the market but in the eyes of the viewer, simply through the subconscious communication that happens when care and intention are translated through the evidence of time and work.

Pump-and-dump is considered a crime through the “misleading positive statements and artificial inflation” involved in raising the stock’s price. Isolating this statement and removing it from the market, the question for me becomes how inflation and contrived positive statements of value affect the volatility or stability of our material needs. How would the politics of disposability change if inflation meant the elevation of the collective worth of the working class? Expanding out from there, how could inflation lead to restorative justice and abolition?